Normal values for pediatric vital signs may vary with age, gender, height, level of anxiety and the technique that you use measure them. Numerous bodies have worked to create normal reference ranges for vital signs in different age groups, however there is some disagreement between groups as to what is truly normal. A good approach is to keep an approximate normal value in mind, and to always interpret vitals based on the clinical context.

For a more detailed approach to this topic, see our podcast on "Pediatric Vital Signs."

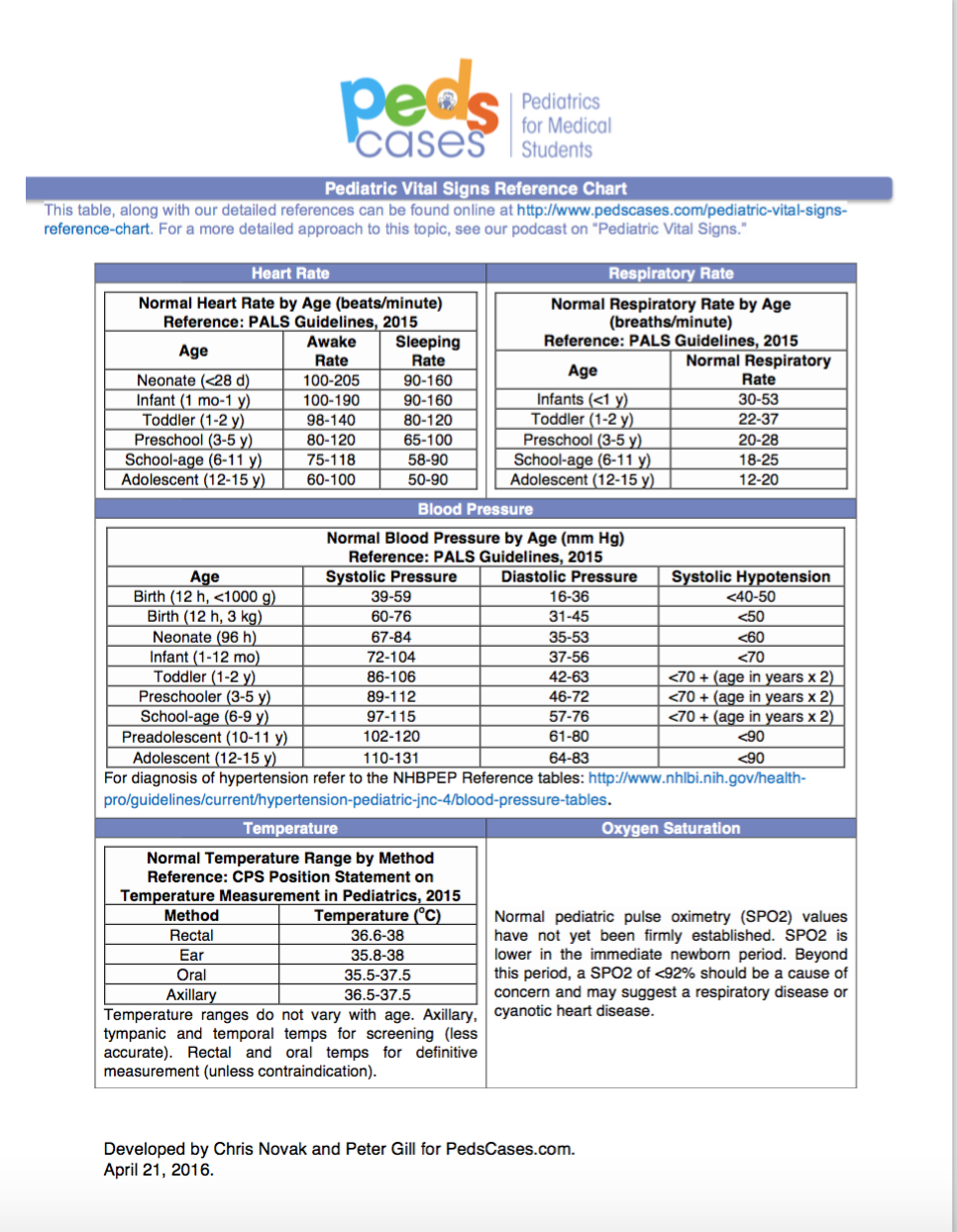

(click the image for a full screen hand-out)

Heart Rate:

Normal Heart Rates By Age (beats/minute) (Reference: Pediatric Advanced Life Support Guidelines) | ||

Age | Awake Rate | Sleeping Rate |

Newborn to 3 months | 85-205 | 80-160 |

3 months to 2 years | 100-190 | 75-160 |

2 to 10 years | 60-140 | 60-90 |

>10 years | 60-100 | 50-90 |

Note: A major 2011 systematic review of pediatric heart rate and respiratory rate suggests that previously published reference ranges may require updating. Updated centile charts based on this study can be found here: http://madox.org/tools-and-resources

Respiratory Rate:

Normal Respiratory Rate By Age (breaths/minute) (Reference: Pediatric Advanced Life Support Guidelines) | |

Age | Normal Respiratory Rate |

Infants (<12 months) | 30-60 |

Toddler (1-3 years) | 24-40 |

Preschool (4-5 years) | 22-34 |

School age (6-12 years) | 18-30 |

Adolescence (13-18 years) | 12-16 |

Note: A major 2011 systematic review of pediatric heart rate and respiratory rate suggests that previously published reference ranges may require updating. Updated centile charts based on this study can be found here: http://madox.org/tools-and-resources

Blood Pressure:

Hypotension Reference Ranges (Reference: Pediatric Advanced Life Support Guidelines) | |

Age | Systolic BP in mm Hg |

Term Neonates (0-28 days) | <60 |

Infants (1-12 months) | <70 |

Children 1-10 years | < 70 + (age in years x 2) |

Children >10 years | <90 |

For precise determination of a child’s blood pressure percentile, as is needed to diagnose hypertension, specific reference ranges have been developed based on a child’s age, gender, and height. You can find these tables here: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/current/hypertension-pediatric-jnc-4/blood-pressure-tables. You can find a handy calculator for determining blood pressure percentiles on UpToDate or other medical apps.

Temperature:

Normal values for temperature do not vary significantly with age. The type of thermometer will alter readings, and accuracy.

Temperature Reference Ranges in Children (Reference: CPS Position Statement on Temperature Measurement in Pediatrics, 2015) | |

Method | Normal Range (oC) |

Rectal | 36.6-38 |

Ear | 35.8-38 |

Oral | 35.5-37.5 |

Axillary | 36.5-37.5 |

The CPS recommends axillary, tympanic and temporal artery thermometers for screening, and rectal and oral thermometers for definitive measurement.

Pulse Oximetry

Normal pediatric pulse oximetry (SPO2) values have not yet been firmly established. SPO2 is lower in the immediate newborn period. Beyond this period, normal levels are stable with age. Generally, a SPO2 of <92% should be a cause of concern and may suggest a respiratory disease or cyanotic heart disease.

References

- Avner, J. Acute Fever. Pediatrics in Review. 2009 Jan 1; 30(1):5-13. Available from: http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/30/1/5.extract

- Chameides L. Pediatrics Advanced Life Support: Provider Manual. American Heart Association; 2012.

- Drutz E. The pediatric physical examination: General principles and standard measurements. UpToDate. 2013 Aug 13 [cited 2015 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/the-pediatric-physical-examination-general-principles-and-standard-measurements

- Fleming S, Thompson M, Stevens R, Heneghan C, Pluddemann A, Maconochie I, Tarassenko L, Mant D. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years: a systematic review of observational studies. Lancet. 2011Mar 19;377(9770):1011-1018.

- Fouzas S, Priftis KN, Anthracopoulos MB. Pulse Oximetry in Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics. 2011 Oct 1; 128(4):740-752. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/128/4/740.full

- Leduc D, Woods S. Temperature measurement in paediatrics.” Canadian Paediatrics Society Position Statement. Posted: 2000 Jan 1. Reaffirmed: 2013 Jan 30 [cited 2015 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/temperature-measurement

- McGee S. Evidence Based Physical Diagnosis, 3rd Edition. Saunders. 2012.

- National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group. Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. National Institute of Health. 2005. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/current/hypertension-pediatric-jnc-4/blood-pressure-tables

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 238.81 KB |